Home > FAQ

Contents

- General Information

- What is JavaCC?

- What is JavaCC used for?

- Where can I get JavaCC?

- Is the source code and documentation for JavaCC publicly available?

- Where can I find books, articles, or tutorials on JavaCC?

- Are there publicly available grammars?

- Is there a user group or mailing list?

- Should I send my questions to the user group?

- Who wrote JavaCC and who maintains it?

- Common Issues

- The Token Manager

- What is a token manager?

- Can I read from a String instead of a file?

- What if more than one regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input?

- What if the chosen regular expression matches more than one prefix?

- What if no regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input?

- How do I make a character sequence match more than one type of token?

- How do I match any character?

- Should I use (~[])+ to match an arbitrarily long sequence of characters?

- How do I match exactly n repetitions of a regular expression?

- What are TOKEN, SKIP, and SPECIAL_TOKEN?

- What are lexical states?

- Can the parser force a switch to a new lexical state?

- Is there a way to make SwitchTo safer?

- What is MORE?

- Why do the example Java and C++ token managers report an error when the last line of a file is a single line comment?

- What is a lexical action?

- How do I tokenize nested comments?

- What is a common token action?

- How do I throw a ParseException instead of a TokenMgrError?

- Why are line and column numbers not recorded?

- Can I process Unicode?

- The Parser and Lookahead

- Where should I draw the line between lexical analysis and parsing?

- What is recursive descent parsing?

- What is left-recursion and why can’t I use it?

- How do I match an empty sequence of tokens?

- What is “lookahead”?

- I get a message saying “Warning: Choice Conflict … “ what should I do?

- I added a LOOKAHEAD specification and the warning went away, does that mean I fixed the problem?

- Are nested syntactic lookahead specifications evaluated during syntactic lookahead?

- Are parameters passed during syntactic lookahead?

- Are semantic actions executed during syntactic lookahead?

- Is semantic lookahead evaluated during syntactic lookahead?

- Can local variables (including parameters) be used in semantic lookahead?

- How does JavaCC differ from standard LL(1) parsing?

- How do I communicate from the parser to the token manager?

- How do I communicate from the token manager to the parser?

- What does it mean to put a regular expression within a BNF production?

- When should regular expressions be put directly into a BNF production?

- How do I parse a sequence without allowing duplications?

- How do I deal with keywords that aren’t reserved?

- There’s an error in the input, so why doesn’t my parser throw a ParseException?

- Semantic Actions

- JJTree and JTB

- Applications of JavaCC

- Comparing JavaCC

- Footnotes

- Acknowledgments

General Information

What is JavaCC?

Java Compiler Compiler (JavaCC) is the most popular parser generator for use with Java applications.

A parser generator is a tool that reads a grammar specification and converts it to a Java program that can recognize matches to the grammar.

In addition to the parser generator itself, JavaCC provides other standard capabilities related to parser generation such as tree building (via a tool called JJTree included with JavaCC), actions, and debugging.

All you need to run a JavaCC parser, once generated, is a Java Runtime Environment (JRE).

JavaCC is particularly useful when you have to write code to deal with an input format that has a complex structure, when hand-crafting a parser without the help of a parser generator would be a difficult job. JavaCC reads a description of the language specification (expressed in Extended BNF) and generates Java code that can read and analyze that language.

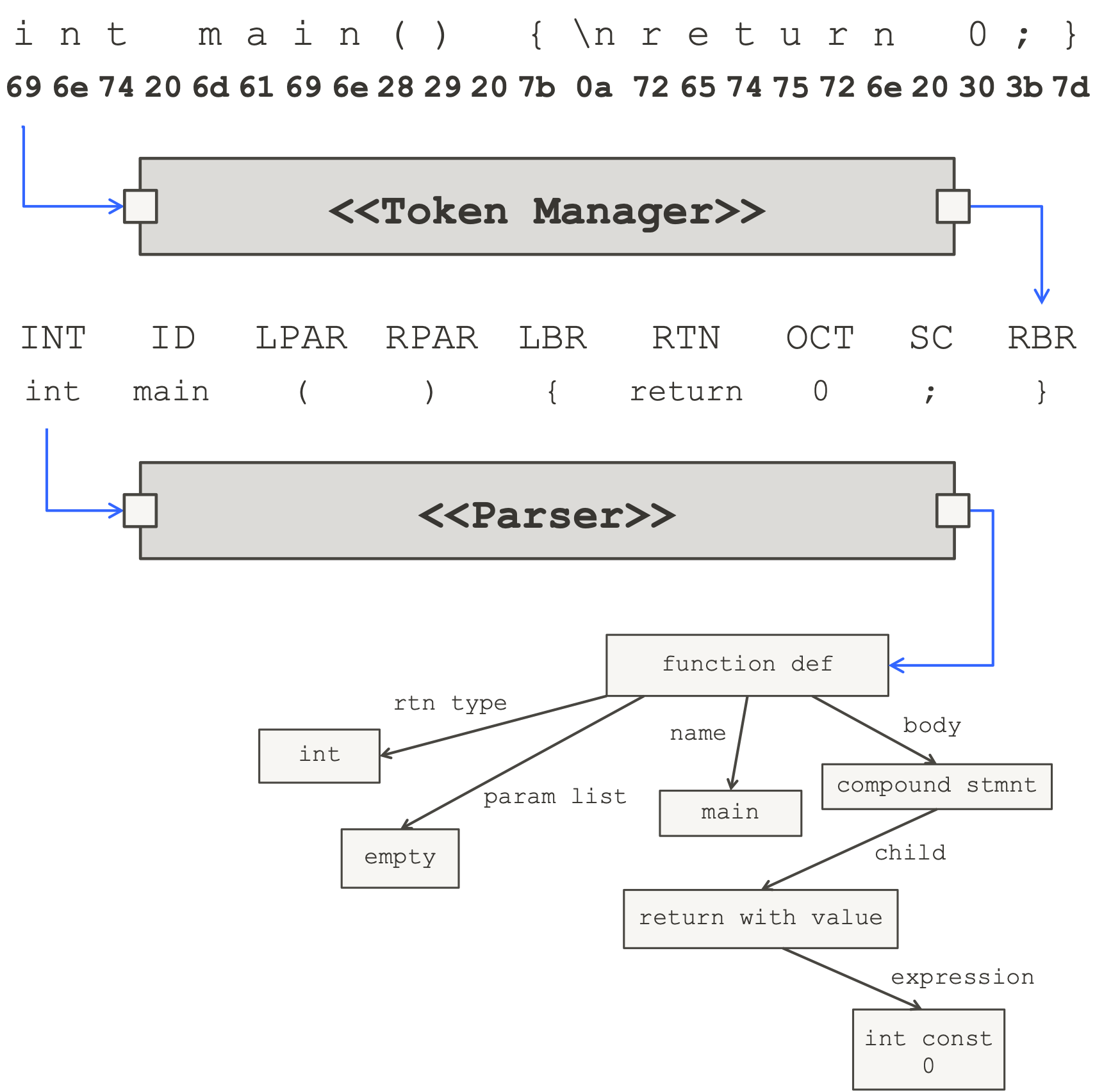

The following diagram shows the relationship between a JavaCC generated lexical analyzer (called a token manager in JavaCC parlance) and a JavaCC generated parser. The diagrams show the C programming language as the input, but JavaCC can handle any language (and not only programming languages) if you can describe the rules of the language to JavaCC.

JavaCC design

The token manager reads in a sequence of characters and produces a sequence of objects called tokens. The rules used to break the sequence of characters into a sequence of tokens depends on the language - they are supplied by the user as a collection of regular expressions.

The parser consumes a sequence of tokens, analyses its structure, and produces an output defined by the user - JavaCC is completely flexible in this regard1.

The diagram shows an abstract syntax tree, but you might want to produce, say, a number (if you are writing a calculator), a file of assembly language (if you were writing a one-pass compiler), a modified sequence of characters (if you were writing a text processing application), and so on.

The user defines a collection of Extended BNF production rules that JavaCC uses to generate the parser as a Java class. These production rules can be annotated with snippets of Java code, which is how the programmer tells the parser what to output produce.

What is JavaCC used for?

JavaCC has been used to create many types of parsers based on formal and proprietary specifications.

| Type | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Programming Languages | Ada, C, C++, COBOL, cURL, Java, JavaScript, Oberon, PHP, Python, Visual Basic |

| Query Languages | SQL, PLSQL, SPARQL, OQL, XML-QL, XPath, XQuery |

| Document Schemas | JSON, XML, DTDs, HTML, RTF, XSLT |

| Messaging Schemas | ASN.1, Email, FIX, SWIFT, RPC |

| Modelling Languages | EXPRESS, IDL, MDL, STEP, ODL, VHDL, VRML |

| Other | Configuration files, templates, calculators etc |

N.B.

-

JavaCC does not automate the building of trees (or any other specific parser output). There are at least two tree building tools (see JJTree and JTB) based on JavaCC, and building trees by hand with a JavaCC based parser is straightforward.

-

JavaCC does not build symbol tables, although if you want a symbol table for a language, then a JavaCC based parser can provide a good framework.

-

JavaCC does not generate output languages. However, once you have a tree structure, it is straightforward to generate output from it.

Where can I get JavaCC?

JavaCC is available from https://javacc.github.io/javacc/.

Is the source code and documentation for JavaCC publicly available?

Yes. The source code and documentation is available on GitHub.

As of June 2003, JavaCC is an open source project released under the BSD License 2.0.

JavaCC is redistributable and there are essentially no restrictions on the use of JavaCC. You may use the Java files that JavaCC produces in any way, including incorporating them into a commercial product.

Where can I find books, articles, or tutorials on JavaCC?

Books

- Dos Reis, Anthony J., Compiler Construction Using Java, JavaCC, and Yacc., Wiley-Blackwell 2012. ISBN 0-4709495-9-7 (book, pdf).

- Copeland, Tom, Generating Parsers with JavaCC., Centennial Books, 2007. ISBN 0-9762214-3-8 (book).

Tutorials

- JavaCC tutorials.

- Introduction to JavaCC by Theodore S. Norvell.

- Incorporating language processing into Java applications: a JavaCC tutorial by Viswanathan Kodaganallur.

Articles

- Looking for lex and yacc for Java? You don’t know Jack by Chuck Mcmanis.

- Build your own languages with JavaCC by Oliver Enseling.

- Writing an Interpreter Using JavaCC by Anand Rajasekar.

- Building a lexical analyzer with JavaCC by Keyvan Akbary.

Parsing theory

- Alfred V. Aho, Monica S. Lam, Ravi Sethi and Jeffrey D. Ullman, Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools, 2nd Edition, Addison-Wesley, 2006, ISBN 0-3211314-3-6 (book, pdf).

- Charles N. Fischer and Richard J. Leblanc, Jr., Crafting a Compiler with C., Pearson, 1991. ISBN 0-8053216-6-7 (book).

Are there publicly available grammars?

Yes. Please see the example grammars and the JavaCC grammar repository.

Is there a user group or mailing list?

Yes. You can contact the JavaCC on the Google user group or email us at JavaCC Support if you need any help.

If you found a bug in JavaCC, please open an issue.

Should I send my questions to the user group?

For questions relating to JavaCC, JJTree, or JTB that are not already covered in the documentation or this FAQ, please use the Google user group. You need to register to join the group.

For questions relating to development please join our Slack channel.

The Google group and Slack channel are not suitable for discussing the Java programming language or javac (the Java compiler), or any other topic that does not relate directly to JavaCC.

General questions on parser generation or parsing theory should be addressed to the comp.compilers Google group.

Who wrote JavaCC and who maintains it?

The JavaCC project was originally developed at Sun Microsystems Inc. by Sreeni Viswanadha and Sriram Sankar.

It is maintained by the developer community which includes the original authors and Chris Ainsley, Tim Pizney, Francis Andre and Marc Mazas.

Common Issues

What files does JavaCC generate?

JavaCC is a program generator. It reads a .jj file and, if that .jj file is error free, produces a number of Java source files. With the default options it will generate the following files:

Boilerplate files

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| SimpleCharStream.java | Represents the stream of input characters. |

| Token.java | Represents a single input token. |

| TokenMgrError.java | An error thrown from the token manager. |

| ParseException.java | An exception indicating that the input did not conform to the parser’s grammar. |

Custom files

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| XXX.java | The parser class. |

| XXXTokenManager.java | The token manager class. |

| XXXConstants.java | An interface associating token classes with symbolic names. |

N.B. XXX is whatever name you choose.

Options

If you use the option JAVA_UNICODE_ESCAPE then SimpleCharStream.java will not be produced, but rather JavaCharStream.java. Prior to version 2.1, one of four possible files was generated: ASCII_CharStream.java, ASCII_UCodeESC_CharStream.java, UCode_CharStream.java, or UCode_UCodeESC_CharStream.java).

If you use the option USER_CHAR_STREAM, then CharStream.java (an interface) will be produced instead of the class SimpleCharStream.java.

Similarly, the option USER_TOKEN_MANAGER will cause the generation of an interface TokenManager.java, rather than a concrete token manager.

The boilerplate files will only be produced if they don’t already exist. There are two important consequences:

- If you make any changes that might require changes to these files, you should delete them prior to running JavaCC (see I changed option X, why am I having trouble?).

- If you really want to, you can modify these files and be sure that JavaCC won’t overwrite them (see Can I modify the generated files?).

Can I modify the generated files?

Modifying any generated files should generally be avoided, since some day you will likely want to regenerate them and then you’ll have to re-modify them.

That said, modifying the Token.java, ParseException.java and TokenMgrError.java files is a fairly safe thing to do as the contents of these files do not depend on the options or the contents of the specification file, other than the package declaration. Modifying the SimpleCharStream.java (or JavaCharStream.java) file should not be done until you are certain of your options, especially the STATIC and JAVA_UNICODE_ESCAPE options.

The custom files (XXX.java, XXXTokenManager.java, and XXXConstants.java) are generated every time you run JavaCC. Modifying any of the custom files is generally a very bad idea, as you’ll have to modify them again after any change to the grammar specification.

I changed option X, why am I having trouble?

This issue usually comes up when the STATIC option is changed - JavaCC needs to generate new files, but it will not generate boilerplate files unless they aren’t there already. Try deleting all files generated by JavaCC (see What files does JavaCC generate?) and then re-running JavaCC.

How do I put the generated classes in a package?

Put a package declaration right after the PARSER_BEGIN(XXX) declaration in the .jj file.

How do I use JavaCC with Ant?

- Download and install Ant from http://ant.apache.org (we require version 1.5.3 or above). This comes with a pre-built JavaCC step documented under the Optional Tasks category.

The Ant task only invokes JavaCC if the grammar file is newer than the generated Java files. The Ant task assumes that the Java class name of the generated parser is the same as the name of the grammar file, ignoring the .jj. If this is not the case, the javacc task will still work, but it will always generate the output files.

- Create a

build.xmlfile which calls the step namedjavacc. Note that capitalization is important and that the Ant documentation for this step is titled JavaCC although the step name isjavacc(the example in the documentation is right).

Assuming you have installed JavaCC in /usr/local/ on a Unix machine, a simple step will look like:

<javacc target="${sampleDir}/SimpleExamples/SimpleExample.jj"

outputdirectory="${sampleDir}/SimpleExamples/java"

javacchome="/usr/local/javacc/7.0.5"

/>

Ant makes it easy to put the generated files in a separate directory. The javacchome attribute defines where you installed JavaCC.

This will need to be followed by a javac step to compile the generated files.

<javac srcdir="${sampleDir}/SimpleLevels/java"

destdir="${sampleDir}/SimpleLevels/classes"

/>

Before running Ant you must add the JavaCC .zip file to your classpath. The JavaCC step does not take a <classpath> modifier, so adding it to the global classpath is the only way to get this information into the step.

$ CLASSPATH=$CLASSPATH:/usr/local/javacc/7.0.5/bin/lib/JavaCC.zip

$ export CLASSPATH

Now all you have to do is issue the command ant.

A complete build.xml file is as follows:

<project name="SimpleExamples" default="compile" basedir="/usr/local/javacc/7.0.5/examples/SimpleExamples">

<!-- properties -->

<property name="sampleDir" value="."/>

<property name="JavaCChome" value="/usr/local/javacc/7.0.5"/>

<!-- initialize -->

<target name="init">

<mkdir dir="${sampleDir}/java"/>

<mkdir dir="${sampleDir}/classes"/>

</target>

<!-- compile -->

<target name="compile" depends="init">

<javacc target="${sampleDir}/SimpleExample.jj" outputdirectory="${sampleDir}/java" javacchome="${JavaCChome}"> </javacc>

<javac srcdir="${sampleDir}/java" destdir="${sampleDir}/classes"/>

</target>

</project>

Can I use JavaCC with my IDE?

IntelliJ IDEA

The IntelliJ IDE supports Ant and Maven out of the box and offers a plugin for JavaCC development.

- IntelliJ download: https://www.jetbrains.com/idea/

- IntelliJ JavaCC Plugin: https://plugins.jetbrains.com/plugin/11431-javacc/

Eclipse IDE

- Eclipse download: https://www.eclipse.org/ide/

- Eclipse JavaCC Plugin: https://marketplace.eclipse.org/content/javacc-eclipse-plug

The Token Manager

What is a token manager?

In conventional compiler terminology, a token manager is a lexical analyzer. The token manager analyzes the input stream of characters, breaking it up into chunks called tokens and assigning each token a type.

Example

Suppose the input file is a C program:

int main() {

/* a short program */

return 0;

}

The token manager might break this into the following tokens:

"int", " ", "main", "(", ")", " ", "{", "\n", " ", "/* a short program */", ... etc

Whitespace and comments are typically discarded, so the tokens are then:

"int", "main", "(", ")", "{", "return", "0", ";", "}"

Each token is classified as one of a finite set of types2. For example, the tokens above could be classified as, respectively,

KWINT, ID, LPAR, RPAR, LBRACE, KWRETURN, OCTALCONST, SEMICOLON, RBRACE

Each token is represented by an object of class Token, each with the following attributes:

.kind // the token type encoded as an int

.image // the chunk of input text as a String

This sequence of Token objects is produced based on regular expressions defined in the .jj file. The sequence is usually sent on to a parser for further processing.

Can I read from a String instead of a file?

Yes. You can do this with a java.io.StringReader as follows:

import java.io.Reader;

import java.io.BufferedReader;

import java.io.StringReader;

/**

* Call a JavaCC generated parser with a String as input

*/

public class MyApp {

String input = "int main() {\n /* a short program */\n return 0;\n}";

public static void main(String[] args) {

Reader reader = new BufferedReader(new StringReader(input));

XXX parser = new XXX(reader);

}

//...

}

What if more than one regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input?

Definition

If a sequence x can be constructed by concatenating two other sequences y and z (i.e. x = yz), then y is called a prefix of x (either y or z can be empty sequences).

Rules

There are three rules for picking which regular expression to use to identify the next token:

- The regular expression must describe a prefix of the remaining input stream.

- If more than one regular expression describes a prefix, then a regular expression that describes the longest prefix of the input stream is used (this is called the maximal munch rule).

- If more than one regular expression describes the longest possible prefix, then the regular expression that comes first in the

.jjfile is used.

Example 1

Suppose you are parsing a Java, C, or C++ program. The following three regular expression productions might appear in the .jj file:

TOKEN : {

< PLUS : "+" >

} // production 1

TOKEN : {

< ASSIGN : "=" >

} // production 2

TOKEN : {

< PLASSIGN : "+=" >

} // production 3

Suppose the remaining input stream starts with:

"+=1; ..."

- Rule 1 rules out the production 2.

- Rule 2 says that production 3 is preferred over the first.

- The order of the productions has no effect on this example.

Example 2

Sticking with Java, C, or C++, suppose you have regular expression productions:

TOKEN : {

< KWINT : "int" >

} // production 1

TOKEN : {

< IDENT : ["a"-"z","A"-"Z", "_"] (["a"-"z","A"-"Z","0"-"9","_"])* >

} // production 2

Suppose the remaining input steams starts with:

"integer i; ..."

Production 1 would be preferred by the maximal munch rule (Rule 2).

But, if the remaining input stream starts with:

"int i; ..."

Then the maximal munch rule is no help, since both rules match a prefix of length 3.

In this case the KWINT production is preferred (by Rule 3) because it comes first in the .jj file.

What if the chosen regular expression matches more than one prefix?

Then the longest prefix is used. That is, the token’s image will be the longest prefix of the input that matches the chosen regular expression.

What if no regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input?

If the remaining input is empty, an EOF token is generated. Otherwise, a TokenMgrError is thrown.

How do I make a character sequence match more than one type of token?

A common misapprehension is that the token manager will make its decisions based on what the parser expects. Given the following token definitions:

TOKEN : {

< A : "x" | "y" >

}

TOKEN : {

< B : "y" | "z" >

}

you might expect the token manager to interpret y as an A if the parser expects an A and as a B if the parser expects a B.

This is not how JavaCC works3. As discussed previously, the first match wins (see What if more than one regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input?).

So what do you do? Let’s consider the more general situation where a and b are regular expressions, and we have the following token definitions:

TOKEN : {

< A : a >

}

TOKEN : {

< B : b >

}

Suppose that a describes a set A and b describes a set B. Then (ignoring other regular expressions) A matches A but B matches B−A. You want the parser to be able to request a member of set B. If A is a subset of B there is a simple solution - create a non-terminal:

Token b() : {

Token t ;

}

{

( t = < A > | t = < B > ) { return t; }

}

Now use b() instead of < B > when you want a token in the set B.

If A is not a subset of B, there is more work to do. Create regular expressions a′, b′, and c′ matching sets A′, B′, C′ such that:

A = C′ ∪ A′

and

B = C′ ∪ (B′−A′)

Now you can write the following productions:

TOKEN : {

< C : c′ >

}

TOKEN : {

< A : a′ >

}

TOKEN : {

< B : b′ >

}

Token a() : {

Token t;

}

{

( t = < C > | t = < A > ) { return t; }

}

Token b() : {

Token t;

}

{

( t = < C > | t = < B > ) { return t; }

}

Use a() when you need a member of set A and b() when you need a member of set B. Applied to the original example, we have:

TOKEN : {

< C : "y" >

}

TOKEN : {

< A : "x" >

}

TOKEN : {

< B : "z" >

}

Token a() : {

Token t;

}

{

( t = < C > | t = < A > ) { return t; }

}

Token b() : {

Token t;

}

{

( t = < C > | t = < B > ) { return t; }

}

This idea can be generalized to any number of overlapping sets.

There are two other approaches that might also be tried - one involves lexical states and the other involves semantic actions.

All three approaches are discussed in How do I deal with keywords that aren’t reserved? which considers a special case of the problem discussed here.

How do I match any character?

Use ~[].

Should I use (~[])+ to match an arbitrarily long sequence of characters?

You might be tempted to use (~[])+. This will match all characters up to the end of the file provided there are more than zero, which is likely not what you want (see What if the chosen regular expression matches more than one prefix?). Usually, what you really want is to match all characters up to either the end of the file or some stopping point.

Consider a scripting language in which scripts are embedded in an otherwise uninterpreted text file set off by " < < " and " > > " tokens. Between the start of the file or a " > > " and the next " < < " or the end of file we need to match an arbitrarily long sequence that does not contain two " < " characters in a row.

We could use a regular expression:

(~[" < "]| " < "~[" < "])+

We don’t want to match this regular expression within a script and so we would use lexical states to separate tokenizing within scripts from tokenizing outside of scripts (see What are lexical states?).

A simpler method uses ~[] and moves the repetition up to the grammar level. Note that the TEXT tokens are all exactly one character long.

< DEFAULT > TOKEN : {

< STARTSCRIPT : " < < " > : SCRIPT

}

< DEFAULT > TOKEN : {

< TEXT : ~[] >

}

< SCRIPT > TOKEN : {

< ENDSCRIPT : " > > " > : DEFAULT

}

// other TOKEN and SKIP productions for the SCRIPT state

Then the grammar is, in part:

void start() : {}

{

text()

(

( < STARTSCRIPT > script() < ENDSCRIPT > )*

text()

)

< EOF >

}

void text() : {}

{

( < TEXT > )*

}

How do I match exactly n repetitions of a regular expression?

If X is the regular expression and n is an integer constant, write:

(X){n}

You can also give a lower and upper bound on the number of repetitions:

(X){l,u}

This syntax applies only to the tokenizer, it can’t be used for parsing.

Note that this syntax is implemented essentially as a macro, so (X){3} is implemented the same as (X)(X)(X) is. Therefore, you should use it with discretion - aware that it can lead to a big generated tokenizer.

What are TOKEN, SKIP, and SPECIAL_TOKEN?

Regular expression productions are classified as one of four types:

TOKENmeans that when the production is applied, aTokenobject should be created and passed to the parser.SKIPmeans that when the production is applied, noTokenobject should be constructed.SPECIAL_TOKENmeans that when the production is applied aTokenobject should be created but it should not be passed to the parser. Each of these special tokens can be accessed from the nextTokenproduced (whether special or not), via itsspecialTokenfield.MOREis discussed in What is MORE?.

What are lexical states?

Lexical states allow you to bring different sets of regular expression productions in-to and out-of effect.

Suppose you wanted to write a JavaDoc processor. Most of Java is tokenized according to regular ordinary Java rules. But between a /** and the next */ a different set of rules applies in which keywords like @param must be recognized and where newlines are significant.

To solve this problem, we could use two lexical states - one for regular Java tokenizing and one for tokenizing within JavaDoc comments.

We can use the following productions:

// when /** is seen in the DEFAULT state, switch to the IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT state

TOKEN : {

< STARTDOC : "/**" > : IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT

}

// when @param is seen in the IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT state, it is a token.

// Stay in the same state.

< IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT > TOKEN : {

< PARAM : "@param" >

}

...

// when */ is seen in the IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT state, switch back to the DEFAULT state

< IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT > TOKEN : {

< ENDDOC: "*/" > : DEFAULT

}

Productions that are prefixed by < IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT > apply when the lexical analyzer is in the IN_JAVADOC_COMMENT state.

Productions that have no such prefix apply in the DEFAULT state. It is possible to list any number of states (comma separated) before a production. The special prefix < * > indicates that the production can apply in all states.

Lexical states are also useful for avoiding complex regular expressions.

Suppose you want to skip C style comments. You could write a regular expression production:

SKIP : { < "/*"(~["*"])* "*"(~["/"] (~["*"])* "*")* "/" > }

But how confident are we that this is right?4 The following version uses a lexical state called IN_COMMENT to make things much clearer:

// when /* is seen in the DEFAULT state, skip it and switch to the IN_COMMENT state

SKIP : {

"/*": IN_COMMENT

}

// when any other character is seen in the IN_COMMENT state, skip it.

< IN_COMMENT > SKIP : {

< ~[] >

}

// when */ is seen in the IN_COMMENT state, skip it and switch back to the DEFAULT state

< IN_COMMENT > SKIP : {

"*/": DEFAULT

}

The previous example also illustrates a subtle behavioural difference between using lexical states and performing the same task with a single, apparently equivalent, regular expression.

Consider tokenizing the C statement:

i = j //* p;

Assuming that there are no occurrences of */ later in the file, this is an error (since a comment starts, but doesn’t end) and should be diagnosed. If we use a single, complex regular expression to find comments, then the lexical error will be missed and, in this example at least, a syntactically correct sequence of seven tokens will be found.

If we use the lexical states approach then the behaviour is different (although again incorrect) as the comment will be skipped - an EOF token will be produced after the token for j and no error will be reported by the token manager5.

We can correct the lexical states approach with the use of MORE (see What is MORE?).

Can the parser force a switch to a new lexical state?

Yes, but it is very easy to create bugs by doing so. You can call the token manager’s method SwitchTo from within a semantic action in the parser like this:

{

token_source.SwitchTo(name_of_state);

}

However, owing to lookahead, the token manager may be well ahead of the parser. During parsing there are a number of tokens waiting to be used by the parser - technically this is a queue of tokens held within the parser object.

Any change of state will take effect for the first token not yet in the queue. Usually there is one token in the queue, but because of syntactic lookahead there may be many more.

If you are going to force a state change from the parser be sure that at that point in the parsing the token manager is a known and fixed number of tokens ahead of the parser, and that you know what that number is.

If you ever feel tempted to call SwitchTo from the parser, stop and try to think of an alternative method that is harder to get wrong.

Is there a way to make SwitchTo safer?

Yes. The following code makes sure that when a SwitchTo is done any queued tokens are removed from the queue.

There are three parts to the solution:

- In the parser add a subroutine

SetStateto change states within semantic actions of the parser.

// JavaCC method for doing lexical state transitions syntactically

private void SetState(int state) {

if (state != token_source.curLexState) {

Token root = new Token(), last = root;

root.next = null;

// first build a list of tokens to push back, in backwards order

while (token.next != null) {

Token t = token;

// find the token whose token.next is the last in the chain

while (t.next != null && t.next.next != null)

t = t.next;

// put it at the end of the new chain

last.next = t.next;

last = t.next;

// if there are special tokens, these go before the regular tokens,

// so we want to push them back onto the input stream in the order

// we find them along the specialToken chain.

if (t.next.specialToken != null) {

Token tt=t.next.specialToken;

while (tt != null) {

last.next = tt;

last = tt;

tt.next = null;

tt = tt.specialToken;

}

}

t.next = null;

};

while (root.next != null) {

token_source.backup(root.next.image.length());

root.next = root.next.next;

}

jj_ntk = -1;

token_source.SwitchTo(state);

}

}

- In the token manager add a subroutine:

TOKEN_MGR_DECLS : {

// required by SetState

void backup(int n) {

input_stream.backup(n);

}

}

- Use the

USER_CHAR_STREAMoption and useBackupCharStreamas theCharStreamclass.BackupCharStreamcan be found on GitHub and is defined as follws:

/* Generated By:JavaCC: Do not edit this line. */

/**

* An implementation of interface CharStream. Modified extensively

* to support being able to back up in the buffer. Modified to support

* Unicode input. Convenience one-arg constructor provided.

*/

public final class BackupCharStream implements CharStream {

private static final class Buffer {

int size;

int dataLen, curPos;

char[] buffer;

int[] bufline, bufcolumn;

public Buffer(int n) {

size = n;

dataLen = 0;

curPos = -1;

buffer = new char[n];

bufline = new int[n];

bufcolumn = new int[n];

}

public void expand(int n) {

char[] newbuffer = new char[size + n];

int newbufline[] = new int[size + n];

int newbufcolumn[] = new int[size + n];

try {

System.arraycopy(buffer, 0, newbuffer, 0, size);

buffer = newbuffer;

System.arraycopy(bufline, 0, newbufline, 0, size);

bufline = newbufline;

System.arraycopy(bufcolumn, 0, newbufcolumn, 0, size);

bufcolumn = newbufcolumn;

}

catch (Throwable t) {

throw new Error(t.getMessage());

}

size += n;

}

}

private Buffer bufA, bufB, curBuf, otherBuf, tokenBeginBuf;

private int tokenBeginPos;

private int backupChars;

public static final boolean staticFlag = false;

private int column = 0;

private int line = 1;

private boolean prevCharIsCR = false;

private boolean prevCharIsLF = false;

private java.io.Reader inputStream;

private boolean inputStreamClosed = false;

private final void swapBuf() {

Buffer tmp = curBuf;

curBuf = otherBuf;

otherBuf = tmp;

}

private final void FillBuff() throws java.io.IOException {

// Buffer fill logic:

// If there is at least 2K left in this buffer, just read some more

// Otherwise, if we're processing a token and it either

// (a) starts in the other buffer (meaning it's filled both part of

// the other buffer and some of this one, or

// (b) starts in the first 2K of this buffer (meaning its taken up

// most of this buffer

// we expand this buffer. Otherwise, we swap buffers.

// This guarantees we will be able to back up at least 2K characters.

if (curBuf.size - curBuf.dataLen < 2048) {

if (tokenBeginPos >= 0

&& ((tokenBeginBuf == curBuf && tokenBeginPos < 2048) || tokenBeginBuf != curBuf)) {

curBuf.expand(2048);

} else {

swapBuf();

curBuf.curPos = curBuf.dataLen = 0;

}

}

try {

int i = inputStream.read(curBuf.buffer, curBuf.dataLen, curBuf.size - curBuf.dataLen);

if (i == -1) {

inputStream.close();

inputStreamClosed = true;

throw new java.io.IOException();

} else

curBuf.dataLen += i;

return;

}

catch (java.io.IOException e) {

if (curBuf.curPos > 0)

--curBuf.curPos;

if (tokenBeginPos == -1) {

tokenBeginPos = curBuf.curPos;

tokenBeginBuf = curBuf;

}

if (e.getClass().getName().equals("sun.io.MalformedInputException")) {

// we want to pass this exception through the JavaCC

// parser, since it has a bad exception handling

throw new ParserRuntimeException("MalformedInput", e);

}

throw e;

}

}

@Override

public final char BeginToken() throws java.io.IOException {

tokenBeginPos = -1;

char c = readChar();

tokenBeginBuf = curBuf;

tokenBeginPos = curBuf.curPos;

return c;

}

private final void UpdateLineColumn(char c) {

column++;

if (prevCharIsLF) {

prevCharIsLF = false;

line += (column = 1);

}

else if (prevCharIsCR) {

prevCharIsCR = false;

if (c == '\n') {

prevCharIsLF = true;

}

else {

line += (column = 1);

}

}

switch (c) {

case '\r':

prevCharIsCR = true;

break;

case '\n':

prevCharIsLF = true;

break;

case '\t':

column--;

column += (8 - (column & 07));

break;

default:

break;

}

curBuf.bufline[curBuf.curPos] = line;

curBuf.bufcolumn[curBuf.curPos] = column;

}

@Override

public final char readChar() throws java.io.IOException {

// When we hit the end of the buffer, if we're backing up, we just

// swap, if we're not, we fill.

if (++curBuf.curPos >= curBuf.dataLen) {

if (backupChars > 0) {

--curBuf.curPos;

swapBuf();

}

else {

FillBuff();

}

}

// Don't mask off the high byte

char c = curBuf.buffer[curBuf.curPos];

// No need to update line numbers if we've already processed this char

if (backupChars > 0) {

--backupChars;

}

else {

UpdateLineColumn(c);

}

return (c);

}

@Override

public final int getEndColumn() {

return curBuf.bufcolumn[curBuf.curPos];

}

@Override

public final int getEndLine() {

return curBuf.bufline[curBuf.curPos];

}

@Override

public final int getBeginColumn() {

return tokenBeginBuf.bufcolumn[tokenBeginPos];

}

@Override

public final int getBeginLine() {

return tokenBeginBuf.bufline[tokenBeginPos];

}

@Override

public final void backup(int amount) {

backupChars += amount;

if (curBuf.curPos - amount < 0) {

int addlChars = amount - (inputStreamClosed ? 0 : 1) - curBuf.curPos;

curBuf.curPos = 0;

swapBuf();

curBuf.curPos = curBuf.dataLen - addlChars - 1;

}

else {

curBuf.curPos -= amount;

}

}

public BackupCharStream(java.io.Reader dstream) {

this(dstream, 1, 1, 4096);

}

public BackupCharStream(java.io.Reader dstream, int startline, int startcolumn, int buffersize) {

ReInit(dstream, startline, startcolumn, buffersize);

}

public BackupCharStream(java.io.Reader dstream, int startline, int startcolumn) {

this(dstream, startline, startcolumn, 4096);

}

public void ReInit(java.io.Reader dstream, int startline, int startcolumn, int buffersize) {

inputStream = dstream;

inputStreamClosed = false;

line = startline;

column = startcolumn - 1;

if (bufA == null || bufA.size != buffersize) {

bufA = new Buffer(buffersize);

}

if (bufB == null || bufB.size != buffersize) {

bufB = new Buffer(buffersize);

}

curBuf = bufA;

otherBuf = bufB;

curBuf.curPos = otherBuf.dataLen = -1;

curBuf.dataLen = otherBuf.dataLen = 0;

prevCharIsLF = prevCharIsCR = false;

tokenBeginPos = -1;

tokenBeginBuf = null;

backupChars = 0;

}

public void ReInit(java.io.Reader dstream, int startline, int startcolumn) {

ReInit(dstream, startline, startcolumn, 4096);

}

public void ReInit(java.io.Reader dstream) {

ReInit(dstream, 1, 1, 4096);

}

public BackupCharStream(java.io.InputStream dstream, int startline, int startcolumn, int buffersize) {

this(new java.io.InputStreamReader(dstream), startline, startcolumn, 4096);

}

public BackupCharStream(java.io.InputStream dstream, int startline, int startcolumn) {

this(dstream, startline, startcolumn, 4096);

}

public void ReInit(java.io.InputStream dstream, int startline, int startcolumn, int buffersize) {

ReInit(new java.io.InputStreamReader(dstream), startline, startcolumn, 4096);

}

public void ReInit(java.io.InputStream dstream, int startline, int startcolumn) {

ReInit(dstream, startline, startcolumn, 4096);

}

@Override

public final String GetImage() {

String ret;

if (tokenBeginBuf == curBuf) {

ret = new String(curBuf.buffer, tokenBeginPos, curBuf.curPos - tokenBeginPos + 1);

}

else {

ret = new String(otherBuf.buffer, tokenBeginPos, otherBuf.dataLen - tokenBeginPos);

if (curBuf.curPos < curBuf.dataLen) {

ret += new String(curBuf.buffer, 0, curBuf.curPos + 1);

}

}

return ret;

}

@Override

public final char[] GetSuffix(int len) {

char[] ret = new char[len];

if ((curBuf.curPos + 1) >= len) {

System.arraycopy(curBuf.buffer, curBuf.curPos - len + 1, ret, 0, len);

}

else {

if (otherBuf.dataLen >= len - curBuf.curPos - 1) {

System.arraycopy(otherBuf.buffer,

otherBuf.dataLen - (len - curBuf.curPos - 1),

ret,

0,

len - curBuf.curPos - 1);

}

System.arraycopy(curBuf.buffer, 0, ret, len - curBuf.curPos - 1, curBuf.curPos + 1);

}

return null;

}

@Override

public void Done() {

bufA = bufB = curBuf = otherBuf = null;

}

}

What is MORE?

Regular expression productions are classified as one of four types (TOKEN, SKIP, and SPECIAL_TOKEN are discussed in What are TOKEN, SKIP, and SPECIAL_TOKEN?).

MORE means that no token should be produced yet - instead, the characters matched will form part of the next token to be recognized. MORE means that there will be more to the token. After a sequence of one or more MORE productions have been applied, we must reach a production that is marked TOKEN, SKIP, SPECIAL_TOKEN. The token produced (or not produced in the case of SKIP) will contain the saved up characters from the preceding MORE productions.

Note that if the end of the input is encountered when the token manager is looking for more of a token, then a TokenMgrError is thrown. The assumption made by JavaCC is that the EOF token should correspond exactly to the end of the input, not to some characters leading up to the end of the input.

Let’s revisit and fix the comment example from What are lexical states?. The problem was that unterminated comments were simply skipped rather than producing an error. We can correct this problem using MORE productions to combine the entire comment into a single token.

// when /* is seen in the DEFAULT state, skip it and switch to the IN_COMMENT state

MORE : {

"/*": IN_COMMENT

}

// when any other character is seen in the IN_COMMENT state, skip it.

< IN_COMMENT > MORE : {

< ~[] >

}

// when */ is seen in the IN_COMMENT state, skip it and switch back to the DEFAULT state

< IN_COMMENT > SKIP : {

"*/": DEFAULT

}

Suppose that a file ends with /*a. Then no token can be recognized because the end of file is found when the token manager only has a partly recognized token. Instead a TokenMgrError will be thrown.

Why do the example Java and C++ token managers report an error when the last line of a file is a single line comment?

The file is likely missing a newline character (or the equivalent) at the end of the last line.

These parsers use lexical states and MORE type regular expression productions to process single line comments:

MORE : {

"//": IN_SINGLE_LINE_COMMENT

}

< IN_SINGLE_LINE_COMMENT > SPECIAL_TOKEN : {

< SINGLE_LINE_COMMENT: "\n"|"\r"|"\r\n" > : DEFAULT

}

< IN_SINGLE_LINE_COMMENT > MORE : {

< ~[] >

}

If an EOF is encountered while the token manager is still looking for more of the current token, there should be a TokenMgrError thrown.

Both the Java and the C++ standards agree with the example .jj files, but some compilers are more liberal and do not insist on that final newline.

If you want the more liberal interpretation, try:

SPECIAL_TOKEN : {

< SINGLE_LINE_COMMENT: "//"(~["\n","\r"])* ("\n"|"\r"|"\r\n")? >

}

What is a lexical action?

Sometimes you want some piece of Java code to be executed immediately after a token is matched. Lexical actions are placed immediately after the regular expression in a regular expression production.

Example

TOKEN : {

< TAB : "\t" > { tabcount += 1; }

}

The Java statement { tabcount += 1; } will be executed after the production is applied.

Keep in mind that the token manager may be significantly ahead of the parser (owing to syntactic lookahead), so using lexical actions to communicate from the token manager to the parser requires care (see How do I communicate from the token manager to the parser?).

How do I tokenize nested comments?

The answer lies in the fact that you can use SwitchTo in a lexical action (see Can the parser force a switch to a new lexical state? and What is a lexical action?). This technique might be useful for a number of things, but the example that keeps coming up is nested comments.

Consider a language where comment start with (* and end with *) but can be nested so that:

(* Comments start with (* and end with *) and can nest. *)

is a valid comment.

When *) is found within a comment, it may or may not require us to switch out of the comment processing state.

Start by declaring a counter (declare it static, if you set the STATIC option to true).

TOKEN_MGR_DECLS : {

int commentNestingDepth;

}

When (* is encountered in the DEFAULT state, set the counter to 1 and enter the COMMENT state:

SKIP : {

"(*" { commentNestingDepth = 1; } : COMMENT

}

When (* is encountered in the COMMENT state, increment the counter:

< COMMENT > SKIP : {

"(*" { commentNestingDepth += 1; }

}

When *) is encountered in the COMMENT state, either switch back to the DEFAULT state or stay in the comment state:

< COMMENT > SKIP : {

"*)" {

commentNestingDepth -= 1;

SwitchTo ( commentNestingDepth == 0 ? DEFAULT : COMMENT ) ;

}

}

Finally a rule is needed to mop up all the other characters in the comment:

< COMMENT > SKIP : {

< ~[] >

}

For this problem only a counter was required. For more complex problems one might use a stack of states. The lexer combined with a stack of states has the expressive power of a deterministic push-down automata (DPDA), which is to say you can solve a lot of problems with this technique.

What is a common token action?

A common token action is simply a subroutine that is called after each token is matched. Note that this does not apply to skipped tokens nor to special tokens (see What are TOKEN, SKIP, and SPECIAL_TOKEN?).

Use

options {

COMMON_TOKEN_ACTION = true;

...

}

and

TOKEN_MGR_DECLS : {

void CommonTokenAction(Token token) {

...

}

}

How do I throw a ParseException instead of a TokenMgrError?

If you don’t want any TokenMgrErrors being thrown, try putting a regular expression production at the very end of your .jj file that will match any character:

< * > TOKEN :

{

< UNEXPECTED_CHAR : ~[] >

}

However, this may not do the trick - if you use MORE, it may be hard to avoid TokenMgrErrors altogether. It is best to make a policy of catching TokenMgrErrors as well as ParseExceptions whenever you call an entry point to the parser.

Why are line and column numbers not recorded?

Since version 2.1 you have the option that the line and column numbers will not be recorded in the Token objects. The option is called KEEP_LINE_COLUMN. The default is true, so not knowing about this option shouldn’t hurt you.

Can I process Unicode?

Yes. The following is a summary of the detailed account of Instantiating JavaCC Tokenizers/Parsers to Read from Unicode Source Files.

Ensure that the option UNICODE_INPUT is set to true.

Assuming your input source is a file (or indeed any stream) of bytes, it needs to be converted from bytes to characters using an appropriate decoding method - this can done by an InputStreamReader.

Example

If your input file uses the UTF-8 encoding, then you can create an appropriate reader as follows:

import java.io.Reader;

import java.io.InputStreamReader;

import java.io.FileInputStream;

/**

* Call a JavaCC generated parser with a Unicode file as input

*/

public class MyApp {

File file = "../path/UnicodeInputFile.txt";

public static void main(String[] args) {

Reader reader = new InputStreamReader(new FileInputStream(file), "UTF-8");

// create a SimpleCharStream (for JavaCharStream the modifications

// to this line of code are obvious).

SimpleCharStream charStream = new SimpleCharStream(reader);

// create a token manager and parser

XXXTokenManager tokenManager = new XXXTokenManager(charStream);

XXX parser = new XXX(tokenManager);

}

}

Since JavaCC 4.0 there are constructors that take an encoding as an argument.

The Parser and Lookahead

Where should I draw the line between lexical analysis and parsing?

This question is dependent on the application. A lot of simple applications only require a token manager. However, many people try to do too much with the lexical analyzer, for example they try to write an expression parser using only the lexical analyzer.

What is recursive descent parsing?

JavaCC’s generated parser classes work by the method of recursive descent. This means that each BNF production in the .jj file is translated into a subroutine with roughly the following mandate:

IF there is a prefix of the input sequence of tokens that matches this non-terminal’s definition THEN remove such a prefix from the input sequence ELSE throw a ParseException

The actual prefix matched is not arbitrary but is determined by the rules of JavaCC.

What is left-recursion and why can’t I use it?

Left-recursion is when a non-terminal contains a recursive reference to itself that is not preceded by something that will consume tokens.

The parser class produced by JavaCC works by recursive descent. Left-recursion is banned to prevent the generated subroutines from calling themselves recursively ad-infinitum.

Consider the following obviously left recursive production

void A() : {} {

A() B()

|

C()

}

This will translate to a Java subroutine of the form:

void A() {

if (some condition) {

A();

B();

}

else {

C();

}

}

If the condition is ever true, we have an infinite recursion.

JavaCC will produce an error message if you have left-recursive productions.

The left-recursive production above can be transformed, using looping, to:

void A() : {} {

C() ( B() )*

}

or, using right-recursion, to:

void A() : {} {

C()

A1()

}

void A1() : {} {

[ B() A1() ]

}

where A1 is a new production. General methods for left-recursion removal can be found in any text book on compiling.

How do I match an empty sequence of tokens?

Use {}. Usually you can use optional clauses to avoid the need.

Example

The production

void A() : {} {

B() | {}

}

is the same as the production

void A() : {} {

[ B() ]

}

The former production is useful if there is a semantic action associated with the empty alternative.

What is “lookahead”?

To use JavaCC effectively you have to understand how it looks ahead in the token stream to decide what to do. As a starting point, you should read the lookahead tutorial in the JavaCC documentation.

The following questions of the FAQ address some common problems and misconceptions about lookahead.

I get a message saying “Warning: Choice Conflict … “ what should I do?

Some of JavaCC’s most common error messages go something like this:

Warning: Choice conflict ...

Consider using a lookahead of 2 for ...

Read the message carefully. Understand why there is a choice conflict (choice conflicts will be explained shortly) and take appropriate action. The appropriate action is rarely to use a lookahead of 2. So what is a choice conflict?

Suppose you have a BNF production:

void a() : {} {

< ID > b()

|

< ID > c()

}

When the parser applies this production, it must choose between expanding it to < ID > b() or expanding it to < ID > c(). The default method of making such choices is to look at the next token. But if the next token is of type ID then either choice is appropriate. So you have a choice conflict.

For alternation (i.e. |) the default choice is the first choice - that is, if you ignore the warning, the first choice will be taken every time the next token could belong to either choice. In the above example the second choice is unreachable.

To resolve this choice conflict you can add a LOOKAHEAD specification to the first alternative. For example, if non-terminal b and non-terminal c can be distinguished on the basis of the token after the ID token, then the parser need only lookahead 2 tokens.

You can tell JavaCC this by writing:

void a() : {} {

LOOKAHEAD (2)

< ID > b()

|

< ID > c()

}

But suppose that b and c can start out the same and are only distinguishable by how they end. No predetermined limit on the length of the lookahead will do. In this case, you can use syntactic lookahead. This means you have the parser look ahead to see if a particular syntactic pattern is matched before committing to a choice.

Syntactic lookahead in this case would look like this:

void a() : {} {

// take the first alternative if an < ID > followed by a b() appears next

LOOKAHEAD( < ID > b() )

< ID > b()

|

< ID > c()

}

The sequence < ID > b() may be parsed twice - once for lookahead and then again as part of regular parsing.

Another way to resolve conflicts is to rewrite the grammar. The above non-terminal can be rewritten as:

void a() : {} {

< ID >

( b() | c() )

}

which may resolve the conflict.

Choice conflicts also come up in loops. Consider:

void paramList() : {} {

param()

(

< COMMA > param()

)*

(

( < COMMA > )? < ELLIPSIS >

)?

}

There is a choice of whether to stay in the * loop or to exit it and process the optional ELLIPSIS. But the default method of making the choice based on the next token does not work - a COMMA token could be the first thing seen in the loop body, or it could be the first thing after the loop body. For loops the default choice is to stay in the loop.

To solve this example we could use a lookahead of 2 at the appropriate choice point (assuming a param can not be empty and that one can’t start with an ELLIPSIS.

void paramList() : {} {

param()

(

LOOKAHEAD(2)

< COMMA > param()

)*

(

( < COMMA > )? < ELLIPSIS >

)?

}

We could also rewrite the grammar, replacing the loop with a recursion, so that a lookahead of 1 suffices:

void paramList() : {} {

param()

moreParamList()

}

void moreParamList() : {} {

< COMMA > ( param() moreParamList() | < ELLIPSIS > )

|

( < ELLIPSIS > )?

}

Sometimes the right thing to do is to simply ignore the warning. Consider this classic example, again from programming languages:

void statement() : {} {

< IF > exp() < THEN > statement()

(

< ELSE > statement()

)?

|

// other possible statements...

}

Because an ELSE token could legitimately follow a statement, there is a conflict. The fact that an ELSE appears next is not enough to indicate that the optional < ELSE > statement() should be parsed, therefore there is a conflict. In fact, this conflict arises from an actual ambiguity in the grammar6, in that there are two ways to parse a statement like:

if c > d then if c < d then q := 1 else q := 2

The default for JavaCC parsers is to take an option rather than to leave it, and that turns out to be the right interpretation in this case (at least for C, C++, Java, Pascal, etc).

To suppress the warning you can write:

void statement() : {} {}

< IF > exp() < THEN > statement()

(

LOOKAHEAD ( < ELSE > )

< ELSE > statement()

)?

|

// other possible statements...

}

If you get a warning, first try rewriting the grammar so that a lookahead of 1 will suffice. Only if that is impossible or inadvisable should you resort to adding lookahead specifications.

I added a LOOKAHEAD specification and the warning went away, does that mean I fixed the problem?

No. JavaCC will not report choice conflict warnings if you use a LOOKAHEAD specification. The absence of a warning doesn’t mean that you’ve solved the problem correctly, it just means that you added a LOOKAHEAD specification.

Consider the following example:

void eg() : {} {

LOOKAHEAD (2)

< A > < B > < C >

|

< A > < B > < D >

}

Clearly the lookahead is insufficient (LOOKAHEAD (3) would do the trick), but JavaCC produces no warning. When you add a LOOKAHEAD specification, JavaCC assumes you know what you are doing and suppresses any warnings.

Are nested syntactic lookahead specifications evaluated during syntactic lookahead?

No.

Consider the following grammar:

void start( ) : { } {

LOOKAHEAD ( a() )

a()

< EOF >

|

w()

< EOF >

}

void a( ) : { } {

(

LOOKAHEAD ( w() y() )

w()

|

w() x()

)

y()

}

void w() : {} { "w" }

void x() : {} { "x" }

void y() : {} { "y" }

and an input sequence of wxy. You might expect that this string will be parsed without error, but it isn’t. The lookahead on a() fails so the parser takes the second (wrong) alternative in start. So why does the lookahead on a() fail?

The lookahead specification within a() is intended to steer the parser to the second alternative when the remaining input starts does not start with wy. However, during syntactic lookahead this inner syntactic lookahead is ignored. The parser considers first whether the remaining input wxy is matched by the alternation (w() | w() x()). First it tries the first alternative w() - this succeeds and so the alternation (w() | w() x()) succeeds. Next, the parser does a lookahead for y() on a remaining input of xy - this fails so the whole lookahead on a() fails.

Lookahead does not backtrack and try the second alternative of the alternation. Once one alternative of an alternation has succeeded, the whole alternation is considered to have succeeded - other alternatives are not considered. Nor does lookahead pay attention to nested synactic LOOKAHEAD specifications.

This problem usually comes about when the LOOKAHEAD specification looks past the end of the choice it applies to. So a solution to the above example is to interchange the order of choices like this:

void a() : { } {

(

LOOKAHEAD ( w() x() )

w() x()

|

w()

)

y()

}

Another solution is to distribute so that the earlier choice is longer. In the above example, we can write:

void a() : { } {

LOOKAHEAD ( w() y() )

w() y()

|

w() x() y()

}

Generally it is a bad idea to write syntactic lookahead specifications that look beyond the end of the choice they apply to.

If you have a production:

a → A | B

and you transliterate it into JavaCC as

void a() : {} {

LOOKAHEAD (C)

A | B

}

then it is a good idea that L(C) (the language of strings matched by C) is a set of prefixes of L(A).

That is to say:

∀u ∈ L(C)·∃v ∈ Σ∗·uv ∈ L(A)

In some cases to accomplish this you can put the longer choice first (that is, the choice that doesn’t include prefixes of the other). In other cases you can use distributivity to lengthen the choices.

Are parameters passed during syntactic lookahead?

No.

Are semantic actions executed during syntactic lookahead?

No.

Is semantic lookahead evaluated during syntactic lookahead?

Yes. It is also evaluated during evaluation of LOOKAHEAD( n ) for n > 1.

Can local variables (including parameters) be used in semantic lookahead?

Yes, to a point.

The problem is that semantic lookahead specifications are evaluated during syntactic lookahead (and during lookahead of more than one token). But the subroutine generated to do the syntactic lookahead for a non-terminal will not declare the parameters or the other local variables of the non-terminal. This means that the code to do the semantic lookahead will fail to compile (in this subroutine) if it mentions parameters or other local variables.

So if you use local variables in a semantic lookahead specification within the BNF production for a non-terminal n, make sure that n is not used in syntactic lookahead, or in a lookahead of more than one token.

This is a case of three rights not making a right! It is right that semantic lookahead is evaluated during syntactic lookahead, it is right (or at least useful) that local variables can be mentioned in semantic lookahead, and it is right that local variables do not exist during syntactic lookahead. Yet putting these three features together tricks JavaCC into producing uncompilable code. Perhaps a future version of JavaCC will put these interacting features on a firmer footing.

How does JavaCC differ from standard LL(1) parsing?

First of all, JavaCC is more flexible. It lets you use multi-token lookahead, syntactic lookahead, and semantic lookahead. If you don’t use these features, you’ll find that JavaCC is only subtly different from an LL(1) parser (it does not calculate follow sets in the standard way, and cannot do so as JavaCC has no idea what your starting non-terminal will be).

How do I communicate from the parser to the token manager?

It is usually a bad idea to try to have the parser try to influence the way the token manager does its job. The reason is that the token manager may produce tokens long before the parser consumes them. This is a result of lookahead.

Often the workaround is to use lexical states to have the token manager change its behaviour on its own.

In other cases, the workaround is to have the token manager not change its behaviour and have the parser compensate. For example, when parsing C you need to know if an identifier is a type or not. If you were using Lex and Yacc, you would probably write your parser in terms of token types ID and TYPEDEF_NAME.

The parser will add typedef names to the symbol table after parsing each typedef definition. The lexical analyzer will look up identifiers in the symbol table to decide which token type to use. This works because with Lex and Yacc the lexical analyzer is always one token ahead of the parser. In JavaCC, it is better to just use one token type, ID, and use a non-terminal in place of TYPEDEF_NAME:

void typedef_name() : {} {

LOOKAHEAD (

{

getToken(1).kind == ID && symtab.isTypedefName ( getToken(1).image )

}

)

< ID >

}

But you have to be careful using semantic lookahead like this - it could still cause trouble. Consider doing a syntactic lookahead on non-terminal statement.

If the next statement is something like:

{

typedef int T; T i; i = 0; return i;

}

The lookahead will fail since the semantic action putting T in the symbol table will not be done during the lookahead. Fortunately, in C there should be no need to do a syntactic lookahead on statements.

How do I communicate from the token manager to the parser?

As with communication between from the parser to the token manager, this can be tricky because the token manager is often well ahead of the parser.

For example, if you calculate the value associated with a particular token type in the token manager and store that value in a simple variable, that variable may well be overwritten by the time the parser consumes the relevant token. Instead you can use a queue. The token manager puts information into the queue and the parser takes it out.

Another solution is to use a table. For example, in dealing with #line directives in C or C++, you can have the token manager fill a table indicating on which physical lines the #line directives occur and what the value given by the #line is. Then the parser can use this table to calculate the source line number from the physical line numbers stored in the Tokens.

What does it mean to put a regular expression within a BNF production?

It is possible to embed a regular expression within a BNF production.

Example

// a regular expression production

TOKEN : {

< ABC : "abc" >

}

// a BNF production

void nonterm() : {} {

"abc"

"def"

< (["0"-"9"])+ >

"abc"

"def"

< (["0"-"9"])+ >

}

There are six regular expressions within the BNF production. The first is simply a Java string and is the same string that appears in the earlier regular expression production. The second is simply a Java string, but does not (we will assume) appear in a regular expression production. The third is a complex regular expression. The next three simply duplicate the first three.

The above grammar is essentially equivalent to:

// a regular expression production

TOKEN : {

< ABC : "abc" >

}

TOKEN : {

< ANON0 : "def" >

}

TOKEN : {

< ANON1 : < (["0"-"9"])+ >

}

TOKEN : {

< ANON2 : < (["0"-"9"])+ >

}

// a BNF production

void nonterm() : {} {

< ABC >

< ANON0 >

< ANON1 >

< ABC >

< ANON0 >

< ANON2 >

}

In general terms, when a regular expression is a Java string and identical to a regular expression occurring in a regular expression production7, then the Java string is interchangeable with the token type from the regular expression production.

When a regular expression is a Java string but there is no corresponding regular expression production, then JavaCC essentially makes up a corresponding regular expression production. This is shown by the def which becomes an anonymous regular expression production. Note that all occurrences of the same string end up represented by a single regular expression production.

Finally, consider the two occurrences of the complex regular expression < (["0"-"9"])+ >. Each one is turned into a different regular expression production. This spells trouble, as the ANON2 regular expression production will never succeed (see What if more than one regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input? and When should regular expressions be put directly into a BNF production?).

When should regular expressions be put directly into a BNF production?

If you haven’t already, it is worth reading What does it mean to put a regular expression within a BNF production?.

For regular expressions that are simply strings, you might as well put them directly into the BNF productions, and not bother with defining them in a regular expression production8.

For more complex regular expressions, it is best to give them a name using a regular expression production. There are two reasons for this:

-

The first reason is error reporting. If you give a complex regular expression a name, that name will be used in the message attached to any

ParseExceptionsgenerated. If you don’t give it a name, JavaCC will make up a name like< token of type 42 >. -

The second reason is perspicuity. Consider the following example:

void letter_number_letters() : {

Token letter, number, letters;

}

{

letter= < ["a"-"z"] >

number= < ["0"-"9"] >

letters= < (["a"-"z"])+ >

{

// return some function of letter, number and letters;

}

}

The intention is to be able to parse strings like a9abc. Written this way it is a bit hard to see what is wrong. We can refactor it as:

TOKEN : {

< LETTER : ["a"-"z"] >

}

TOKEN : {

< NUMBER : ["0"-"9"] >

}

TOKEN : {

< LETTERS : (["a"-"z"])+ >

}

void letter_number_letters() : {

Token letter, number, letters;

}

{

letter = < LETTER >

number = < NUMBER >

letters = < LETTERS >

{

// return some function of letter, number and letters ;

}

}

and it might be easier to see the error. On a string like z7d the token manager will find a LETTER, a NUMBER and then another LETTER - the BNF production can not succeed (see What if more than one regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input?).

How do I parse a sequence without allowing duplications?

This turns out to be a bit tricky. You could list all the alternatives. Say you want A, B, C, each optionally, in any order with no duplications - there are only 16 possibilities:

void abc() : {} {

[ < A > [ < B > [ < C > ] ] ]

|

< A > < C > [ < B > ]

|

< B > [ < A > [ < C > ] ]

|

< B > < C > [ < A > ]

|

< C > [ < A > [ < B > ] ]

|

< C > < B > [ < A > ]

}

This approach is difficult to maintain and does not scale well.

A better approach is to use semantic actions to record what has been seen:

void abc() : {} {

(

< A >

{

if ( seen an A already )

throw ParseException("Duplicate A");

else record an A

}

|

< B >

{

if ( seen an B already )

throw ParseException("Duplicate B");

else record an B }

|

< C >

{

if ( seen an C already )

throw ParseException("Duplicate C");

else record an C

}

)*

}

The problem with this approach is that it will not work with syntactic lookahead. Ninety-nine percent of the time you won’t care about this problem, but consider the following highly contrived example:

void toughChoice() : {} {

LOOKAHEAD ( abc() )

abc()

|

< A > < A > < B > < B >

}

When the input is two A’s followed by two B’s, the second choice should be taken. If you use the first version of abc above, then that’s what happens.

If you use the second version of abc then the first choice is taken, since syntactically abc is ( < A > | < B > | < C > )*.

How do I deal with keywords that aren’t reserved?

In Java, C++, and many other languages, keywords like int, if, throw and so on are reserved, meaning that you can’t use them for any purpose other than that defined by the language - in particular you can use them for variable names, function names, class names etc. In some applications, keywords are not reserved.

For example, in the PL/I language, the following is a valid statement:

if if = then then then = else ; else else = if ;

Sometimes you want if, then, and else to act like keywords and sometimes like identifiers.

This is a special case of a more general problem discussed in How do I make a character sequence match more than one type of token?.

For a more modern example - parsing URLs - we might want to treat the word http as a keyword, but we don’t want to prevent it being used as a host name or a path segment.

Suppose we write the following productions9:

TOKEN : {

< HTTP : "http" >

}

TOKEN : {

< LABEL : < ALPHANUM > | < ALPHANUM > ( < ALPHANUM > | "-" )* < ALPHANUM > >

}

void httpURL() : {} {

< HTTP > ":""//"host() port_path_and_query()

}

void host() : {} {

< LABEL > ("." < LABEL > )*

}

Both the regular expressions labelled HTTP and LABEL, match the string http. As covered in What if more than one regular expression matches a prefix of the remaining input? the first rule will be chosen, therefore the URL http://www.http.org/ will not be accepted by the grammar.

So what can you do? There are basically three strategies:

- Put choices in the grammar.

Going back to the original grammar, we can see that the problem is that where we say we expect a LABEL we actually intended to expect either a LABEL or a HTTP.

We can refactor the last production as:

void host() : {} {

label() ("."label())*

}

void label() : {} {

< LABEL > | < HTTP >

}

- Replace keywords with semantic lookahead.

Here we eliminate the offending keyword production. In the example we would eliminate the regular expression production labelled HTTP. Then we have to refactor httpURL as follows:

void httpURL() : {} {

LOOKAHEAD (

{

getToken(1).kind == LABEL && getToken(1).image.equals("http")

}

)

< LABEL > ":""//"host() port_path_and_query()

}

The added semantic lookahead ensures that the URL really begins with a LABEL which is actually the keyword http.

- Use lexical states.

The idea here is to use a different lexical state when the word is reserved and when it isn’t (see What are lexical states?).

We can make http reserved in the default lexical state, but not reserved when a label is expected. In the example this is easy because it is clear when a label is expected - after a // and after a .10. Therefore we can refactor the regular expression productions as:

TOKEN : {

< HTTP : "http" >

}

TOKEN : {

< DSLASH : "//" > : LABELEXPECTED

}

TOKEN : {

< DOT : "." > : LABELEXPECTED

}

< LABELEXPECTED > TOKEN : {

< LABEL : < ALPHANUM > | < ALPHANUM > ( < ALPHANUM > |"-")* < ALPHANUM > > : DEFAULT

}

And the BNF productions are:

void httpURL() : {} {

< HTTP > ":" < DSLASH > host() port_path_and_query()

}

void host() : {} {

< LABEL > ( < DOT > < LABEL > )*

}

There’s an error in the input, so why doesn’t my parser throw a ParseException?

You may have omitted the < EOF > in the production for your start non-terminal.

Semantic Actions

I’ve written a parser, why doesn’t it do anything?

You need to add semantic actions. Semantic actions are bits of Java code that get executed as the parser is parsing.

How do I capture and traverse a sequence of tokens?

Each Token object has a pointer to the next Token object. More precisely, there are two kinds of Token objects:

- Regular token objects created by regular expression productions prefixed by the keyword

TOKEN. - Special token objects created by regular expression productions prefixed by the keyword

SPECIAL_TOKEN.

Each regular Token object has a pointer to the next regular Token object (we will deal with the special tokens below).

Now, since the tokens are nicely linked into a list, we can represent a sequence of tokens occurring in the document with a class by pointing to the first token in the sequence and the first token to follow the sequence.

class TokenList {

private Token head;

private Token tail;

TokenList ( Token head, Token tail ) {

this.head = head;

this.tail = tail;

}

// ...

}

We can create such a list using semantic actions in the parser:

TokenList CompilationUnit() : {

Token head ;

}

{

{

head = getToken(1);

}

[ PackageDeclaration() ] ( ImportDeclaration() )* ( TypeDeclaration() )*

< EOF >

{

return new TokenList( head, getToken(0) );

}

}

To print regular tokens in the list, we can simply traverse the list:

class TokenList {

// ...

void print ( PrintStream os ) {

for ( Token p = head; p != tail; p = p.next ) {

os.print( p.image );

}

}

// ...

}

This method of traversing the list of tokens is appropriate for many applications. Printing the tokens from a Java file would produce the following output:

publicclassToken{publicintkind;publicintbeginLine,

As this output is neither human-readable nor machine-readable, it would be useful to add whitespace. We could just print a space between each pair of tokens, or a nicer solution is to capture all the spaces and comments using special tokens.

Each Token object (whether regular or special) has a field called specialToken which points to the special token that appeared in the text immediately prior, if there was one, and is null otherwise. So, prior to printing the image of each token, we print the image of the preceding special token, if it exists:

class TokenList {

// ...

private void printSpecialTokens ( PrintStream ps, Token st ) {

if ( st != null ) {

printSpecialTokens( ps, st.specialToken );

ps.print( st.image );

}

}

void printWithSpecials( PrintStream ps ) {

for ( Token p = head; p != tail; p = p.next ) {

printSpecialTokens( ps, p.specialToken ) ;

ps.print( p.image );

}

}

// ...

}

If you want to capture and print a whole file, don’t forget about the special tokens that precede the EOF token.

Why does my parser use so much space?

One reason might be that you saved a pointer to a Token like this.

void CompilationUnit() : {

Token name;

}

{

Modifiers()

Type()

name = < ID >

{

System.out.println( name.image );

}

Extends()

Implements()

ClassBody()

}

The variable name is last used in the call to println but it remains on the stack pointing to that token until the generated CompilationUnit() method returns. This means that the ID token can’t be garbage collected until the subroutine returns.

That token has a next field that points to the next token and that one has a next field and so on. So all the tokens from the ID to the end of the class body cannot be garbage collected until the subroutine returns. The solution is simple - add name = null; after the final use of the Token variable and hope that your compiler doesn’t optimize away this dead code.

JJTree and JTB

What are JJTree and JTB?

These are preprocessors that produce .jj files. The .jj files produced will generate parsers that produce trees.

Where can I get JJTree?

JJTree comes with JavaCC (see Where can I get JavaCC?).

Where can I get JTB?

Please see the Java Tree Builder website.

Applications of JavaCC

Where can I find a parser for X?

Please see the example grammars and the JavaCC grammar repository.

How do I parse arithmetic expressions?